The Zen of Film Scoring: The Sonic Palette

During my first week of procrastinating — er, working very hard on the score for I Hate You, I was naturally a bit curious to learn more about the methods and techniques of established composers. Spending time pretending to pick up tips from the pros was an excellent way to avoid the fact that I was freaking out about how the hell I would successfully pull this shit off. One YouTube video wound up being a big inspiration, but not in the way I had initially imagined.

In a roundtable discussion between some incredibly successful Hollywood composers (including Danny Elfman, Hans Zimmer and Trent Reznor), two parts in particular jumped out at me: one was when each of these musicians—again, we're talking about some of the most well-respected composers in the business—expressed their extreme insecurity any time they started a new project. The other was when they revealed that the first thing they do when starting a score is to spend a lot of time panicking and putting the whole thing off.

On the one hand, it sucks that those feelings apparently never go away. But on the other, I was feeling the exact same thing that some of the greatest composers of our time felt, ergo I was clearly already becoming a legit composer of legendary status. Still, while I had already written a small bit of music that was met with enthusiastic approval, I really did have to get something else started. I didn't have the luxury of spending a 40-hour work week on writing music, after all.

Getting Organized: The Score Grid

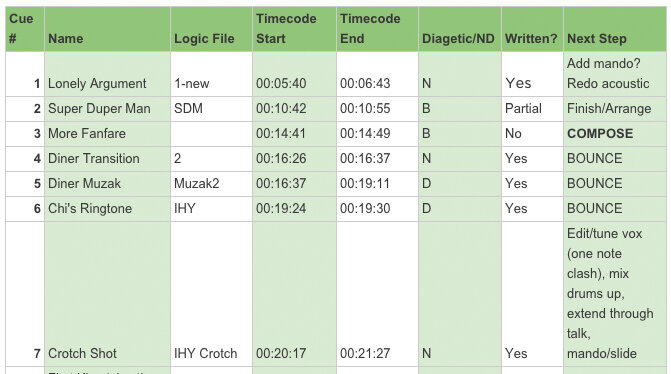

First I needed to get good and organized, which is apparently a thing I enjoy doing. I made a grid containing every music cue I had to tackle and assigned each one a name and number. Then I noted things like the movie timecode start/end times, whether the cue was diagetic, non-diagetic or both (I'll explain what that means in a second), if I had started writing any music for the cue, plus a brief note about what needed to be done next. FYI, diagetic music comes from within the scene itself (like the muzak playing in a diner where the characters are eating) as opposed to the movie score. I pretended to know what that word meant when I talked to the director, then looked it up later so I would seem smart.

I saved this master chart in Evernote and linked to individual notes for each cue where I could write detailed ideas, keep track of feedback from the director and add scratch audio recordings from my phone or perhaps images of motivational posters that say "Don't f#$% this up." I had the grid set up next to my workspace to refer to as I jumped between cues.

Below is a screenshot of part of the grid from about two months ago. And yes, I did name a cue "Crotch Shot." Such custom name designations are the privilege one has when scoring, and it had the added bonus of a long email chain with the subject "CROTCH SHOT" showing up over and over in my inbox.

I should probably note here that I actually didn't even think about diagetic music when I first agreed to score the film. It didn't even occur to me that I would be responsible for creating music inside the scenes themselves, which speaks volumes to my inexperience with scoring features. But the variety of diagetic music in this project really upped the diversity and challenge of the scoring process, which was great. If I wasn't feeling a particular cue at any one time, I could always change gears to write the score for an '80s John Carpenter-esque action movie. Which I did. And it was awesome.

Building The Sonic Palette

One of the first things I needed to do was establish the sonic palette, which is really just a fancy way of saying I had to figure out what instruments I'd be using. With modern sample libraries, the timbral possibilities are nearly endless, but in order for a score to feel cohesive there needs to be some consistency in the sounds you're hearing throughout. Brad, the director, said early on that he wanted the score to be mostly organic, which suited me just fine since I planned to base a lot of it on an acoustic guitar foundation. But since one of the main characters really likes video games, there were certain cues where I wanted to include sounds that threw back to classic video game music without sticking out too much sonically. So several pieces received a subtle synth pad based on a square wave (one of the types of synthesized sounds commonly heard in Nintendo games).

The palette was slowly built in this manner. Often I would find myself using a new instrument for a scene, only to realize that it might sound "out of nowhere" in the context of the movie since it hadn't shown up in any music prior. There was one cue where I used a hammered dulcimer sound, then retroactively added dulcimer to several earlier scenes to find that it fit in rather nicely. I never did find a way to work in a kazoo, though. This has been added to the list of my life's greatest regrets.

Of course, you can go overboard. You don't want to include every sound in every cue. You don't want to force an instrument into a place where it doesn't make sense. You also want to have a few surprises along the way to keep it interesting. So it becomes a balancing act, the art of deciding what goes where and why, and more importantly what doesn't go where. As you do this, the sonic palette comes into focus, and that makes each successive decision easier to make.

Once I got the basics of the sonic palette down, it was off to the races...

By the way, you may have noticed what looked like a tablet computer on a stand displaying my master grid in the photo above, but that's actually a 2-in-1 laptop/tablet hybrid. The fine folks at Intel, who you may remember had me make some music on an all-in-one a few months ago, wanted me to give this Toshiba a try as well. It's a laptop with a touch screen that can be rotated 360 degrees to be used at many angles for things like watching video or using it like a tablet. In the above example, I incorporated it into my music-making process by having the grid on-hand to consult or to look up music-related stuff without using any resources from my recording computer, which can come at a premium when you're using as many software instruments as I do. I updated the computer to Windows 10, which was simple and free. One of the benefits to the upgrade was making it way easier to switch between laptop and tablet mode—very key for a computer like this—while still being a clean and familiar interface.

#spon: I'm required to disclose a relationship between our site and Intel This could include Intel providing us w/content, product, access or other forms of payment.